We sat down with Susan Lafond, a long-time educator and parent of a son — now a young adult — with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Her experience as a parent and as an educator can help teachers, administrators, and support staff better understand how even small strategies or shifts in a classroom environment can change the trajectory for all students, whether they are neurodiverse or traditional learners. The more teachers — and whole schools — strive to create classrooms that are inclusive and equitable for all kinds of learners, the more successful the teaching and the learning will be.

Ms. Lafond is a Nationally Board Certified veteran educator of ELLs, professional development leader, and advisor and contributor to Colorín Colorado — WETA’s bilingual site for educators and families of English language learners.

LD OnLine: No doubt almost every classroom teacher has had — or will have — at least one student with a learning difference like ADHD. Can you tell us about your son and some of his strengths and interests when he was a kid?

Ms. Lafond: Justin was a bright young child, a very sweet boy. He spoke quite early, was very expressive, and had lots of energy and personality. He always enjoyed reading and even as a little kid had a great vocabulary. He also reveled in the mechanical aspects of toys. He loved building and making things. And he was always great at math — those concepts came quickly to him no matter his grade level.

LD OnLine: Can you talk about how and when you and your husband first learned that Justin had ADHD so that teachers can better understand students diagnosed with a learning difference?

Ms. Lafond: It took a while before my husband and I realized that Justin had ADHD. I think the first time we became aware of something was when he was 3 years old and in daycare. We had a parent/teacher conference and were surprised to learn that many of his physical and social behaviors at school didn’t seem to match up with his academic strengths nor his behaviors at home.

In kindergarten, he tested off the charts academically. Unfortunately, our school didn’t offer a talented and gifted program until about third grade. But we were lucky. From kindergarten through second grade, he was placed in classes where he was given lots of one-on-one time with his primary teachers, one in particular who was nationally board-certified educator who found engaging and challenging activities that really helped him thrive.

After a rocky third grade with a rather green teacher who hadn’t yet established her own classroom management style, I decided, when he entered fourth, to pursue the causes of his behavioral issues. Back then, the early 2000s, ADHD was not so prevalent, there wasn’t much information out there, and frankly, I just wanted to figure out why he was struggling socially and behaviorally in school. I’m sure his teachers did, too! The idea of ADHD actually floated into my sphere when my sister-in-law noticed some behavior issues with own her son and had him tested. They thought he might have ADHD, though it turned out it was something completely different, but the ADHD profile on the questionnaires they had filled out turned out to patently describe Justin’s behavior.

I was in denial at first but the seed was planted. As an educator — and a parent — I needed to know more. I checked out every library book I could find on the topic. I sat in bookstores and read and bought the ones I knew I needed to spend more time poring over at home. And having the advantage of being an educator, I sat down with my district Committee on Special Education (CSE) chair, who was a friend, and peppered her with questions. Finally, I formally requested a psychoeducational evaluation for Justin in school in addition to setting up an outside neuropsychological assessment.

He was formally diagnosed with ADHD in fourth grade. Finally having a diagnosis — as hard as it was to hear — was a relief to us and to his teachers. It’s a cliché, but knowledge is power.

LD OnLine: Can you share some of Justin’s biggest challenges at school to illuminate for teachers out there who may be confused about the behavior of one or more of their students?

Ms. Lafond: Number one were his social challenges. As a parent, of course, I wanted him to be accepted, to have friends and a sense of belonging. He wasn’t necessarily following the expectations set out in the classroom, the expectations that his peers seemed to organically understand and accept. So, his behaviors were often off-putting and got in the way of his building positive social relationships. No doubt this was difficult for his teachers.

On the flip side of that, he picked up what was being taught really quickly. He didn’t need the repetition and the practice that many of his peers did. And because he got it so quickly, he would get bored, distract other students, and want to share his fascination with certain related topics that were not necessarily part of the curriculum. The teachers admired his curiosity and intelligence, but it was still disruptive to the group.

LD OnLine: How did you work with teachers as Justin’s advocate?

Ms. Lafond: Early each fall before school started, I would write a letter to the teacher he was going to have that year letting them know about Justin, what they could expect, what his strengths were, and his weaknesses. I wanted them to know the good side, but I also wanted them to understand that some of his behaviors might be problematic and what could help. I always closed the letter by saying that my husband and I wanted to partner with them in support of Justin and of them and the whole class. Teachers juggle so much; I just wanted to make anything that I could a bit easier for them.

Next, I would make sure I attended the open houses at the school, which usually took place two-three weeks after school started. I would introduce myself, remind them of the letter, and in that way, they knew I was serious about wanting to collaborate.

From there, the parent/teacher conferences were an opportunity to check in and problem solve together. And then throughout the year, the teacher and I would have periodic, ongoing communication. Sometimes messages were sent home in his bookbag, sometimes through calls or emails. No matter what, I’d always respond quickly so that we could figure out a plan that worked for everybody. Our strong, consistent communication, I believe, helped all of us feel heard and valued. I wanted a win/win for Justin and for his teachers. As an educator myself, I always appreciated when parents would feel comfortable reaching out to me with questions, concerns, or suggestions.

At the end of the year, the teacher and I would talk about who we thought would be the best teacher for Justin the following year. Our choice was not necessarily the best or most popular teacher, rather the teacher who would work well with Justin. If we had someone who was too permissive, then we knew he was going to push things too far. If we had somebody who was too strict, then I think that would have squelched his creativity. So, I needed someone who would be willing to work with him who would recognize what he had to offer and utilize that. And so, we would do that handpicking, and then I would write a letter to the school principal requesting that teacher but always producing the educational rationale. I was not trying to bypass the school district’s policies, I just wanted to work within them to find the situation that best benefited my son and his educators.

LD OnLine: How did the steps for advocating for Justin change as he got older and into junior and high school — and in what ways do your experiences help other educators work with students with LD?

Ms. Lafond: I still wrote my yearly letter and met with his teachers, but what changed was that I didn’t meet with his teachers separately. Instead, we’d meet as a group, which was always helpful, especially for the teachers themselves. Some teachers who maybe had more experience working with kids with ADHD would offer suggestions, others shared what worked and what didn’t. They’d learn from each other’s experiences and suggestions; their willingness to listen and to try new things made all the difference not only for Justin but also for them as teachers who have and will have classrooms full of neurodiverse learners.

LD OnLine: Did Justin have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and why is it important for teachers to understand the difference between an IEP and a 504 plan?

Ms. Lafond: Justin never had an IEP because he tested off the charts academically, especially in math. He did have a 504 plan, however, which focused on his challenges around executive functioning and self-regulation skills — the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember, and juggle multiple tasks. Organizing his bookbag or leaving an assignment until 9pm on a Sunday night are examples of Justin’s challenges.

When teachers understand a child’s specific challenges, they can offer even small gestures or adjustments in their instruction that can make all the difference.

A 504 plan allows children with special needs who don’t want or qualify for special education services to better access learning experiences at school. An IEP is individualized to meet each child’s needs and applies to special education and related services.

LD OnLine: From your experience as a parent and an educator, what advice would you give to teachers working with students with ADHD like Justin?

Ms. Lafond: I think the most basic nugget of advice that I would suggest would be around flexibility. Try to be flexible in how you think about and respond to that student. What is motivating his behavior … is he disrupting the class on purpose because he is a trouble maker or because he is distracted or bored? As a teacher myself, I know I have had to step back, open my mind, and not take things too personally.

Also, for teachers, stablishing a partnership with parents can help a great deal. Instead of calling a parent to say your child is doing this or that and it’s disruptive, maybe you start by sharing something positive the child is doing and then talk about strategies to help with the behaviors that may be thorny. This kind of collaborative effort spans in and beyond the classroom so the student receives consistent feedback and support — and the teacher feels supported and heard by the parent.

LD OnLine: Looking back, were there things that you wish Justin’s teachers had done differently?

Ms. Lafond: We had a situation where despite Justin’s high scores, one of the teachers in the gifted and talented program wanted Justin out of the program because of his issues with disorganization, his inability to meet deadlines, and his behavior around those challenges. He could certainly do the work and do it well, but his executive functioning problems became an obstacle.

We had a meeting to try to keep him in, but they preferred to have him out of the program. I was not happy about it, but I had to accept it. I know how important it is as a parent and an educator to be an advocate, but I also didn’t want to be the squeaky wheel complaining and finding fault.

Instead, I felt my role was to be the training wheels to the bicycle that helped keep my son in balance on his educational journey, that supported his fight to stay upright as he pedaled through 12 years of education.

LD OnLine: Can you share a bit about Justin’s young adult years?

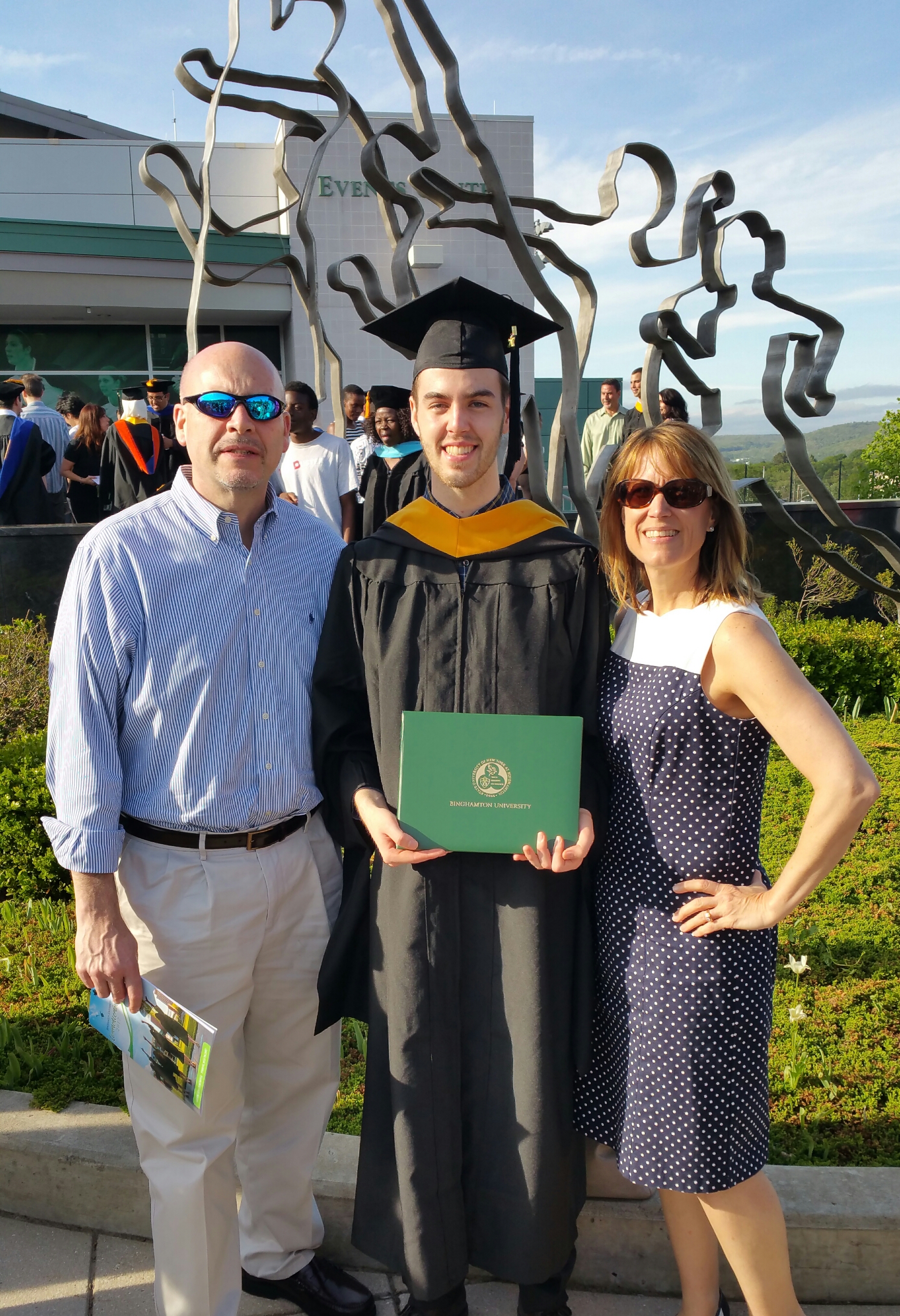

Ms. Lafond: Justin earned an undergraduate degree in Biological Sciences and a master’s in Neuroscience. He completed both in four instead of five years. He’s still figuring out what kind of career he ultimately wants, but right now he helps clients in the gaming industry where he can bring his passion for science and creativity together.

LD OnLine: You are a 20-year teaching veteran — teaching World Languages and French and Spanish in middle and high school. You were also an ENL — English as a New Language — teacher. Can you talk about what you learned about supporting English Language Learners (ELLs) — or ENLs — with ADHD?

Ms. Lafond: As an educator of ELLs, engaging and working with parents and families is absolutely critical. And finding ways to communicate with parents in their preferred method as well as their preferred language is also important. There can be a lot going on … for example, if a family has immigrated here, settling into a new community, a new culture, a new school where the educational system may be very different can be tumultuous, overwhelming, scary. So, the communication and openness a teacher can bring to an ELL family can make a significant difference.

LD OnLine: Any last words of wisdom for educators?

Ms. Lafond: First of all, I would say that each child, no matter how they learn, no matter their passions, no matter their quirks is a special child who deserves to be appreciated for who they are and who they will grow to be. I think especially as schools focus more on creating inclusive classroom environments for all types of learners, teachers appreciate the individuality and specialness in each child.

There’s a quote out there that says, “If a child can’t learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn.” I think that is great advice for every teacher … every person in and beyond the classroom who is dedicated to helping kids learn and succeed.

For everyone

Susan’s son, twentysomething Justin Lafond, sheds his own story about growing up with ADHD.